Poetics of Dying

Poetics of Dying is an educational toolkit created by Amanda Astorga-Pinto, Naoki Hashimoto, and Jenny Liu in collaboration with New York Presbyterian Hospital and Parsons School of Design to teach medical practitioners how to have an honest and open conversation about end of life.

̌

As we live in an age where medical advancements are allowing people to live longer and attitudes are shifting on survival and longevity, issues surrounding dying and end of life care have remained largely unaddressed by non-palliative care doctors. Poetics of Dying addresses the lack of attention and communication around what it means to have “a good end of life” due to over-prioritization of acute interventions and rescue.

Our designed research tools emerged into an educational concept tool that we have been continuing to prototype with medical practitioners in training. We discovered that to truly embody these issues around dying and care, physicians-in-training must allow these insights to come from a form of self-realization of their own biases in language and communication.

To achieve this goal, the tool does not explicitly lay out these key concerns, but creates the conditions that will allow physicians-in-training to arrive at these realizations themselves.

The toolkit can be embedded 1) in a clinical skills course or workshop during medical school or 2) in a resident’s elective course during the first year of training. Instructions are as follows:

1. Set up digital audio recording and transcription software.

2. Select a scenario card and role play the described medical situation.

3. Read through the transcribed dialogue.

4. Search for language patterns using pre-designed keys or identify patterns using self-generated keys from blank templates. Highlight words and themes corresponding to the keys.

5. Discuss findings from exercise with one another.

6. Supplemental: The toolkit provides a reference guide containing several coded transcriptions of recorded conversations about end of life with a palliative care doctor. The guide can be used as inspiration for identifying trends in clinical language.

Understanding that honest doctor-patient conversations are an overlooked area of medical care that carries great personal and financial burden, we began our process by examining how physician attitudes around end of life are formed, starting with the early stages of their medical training.

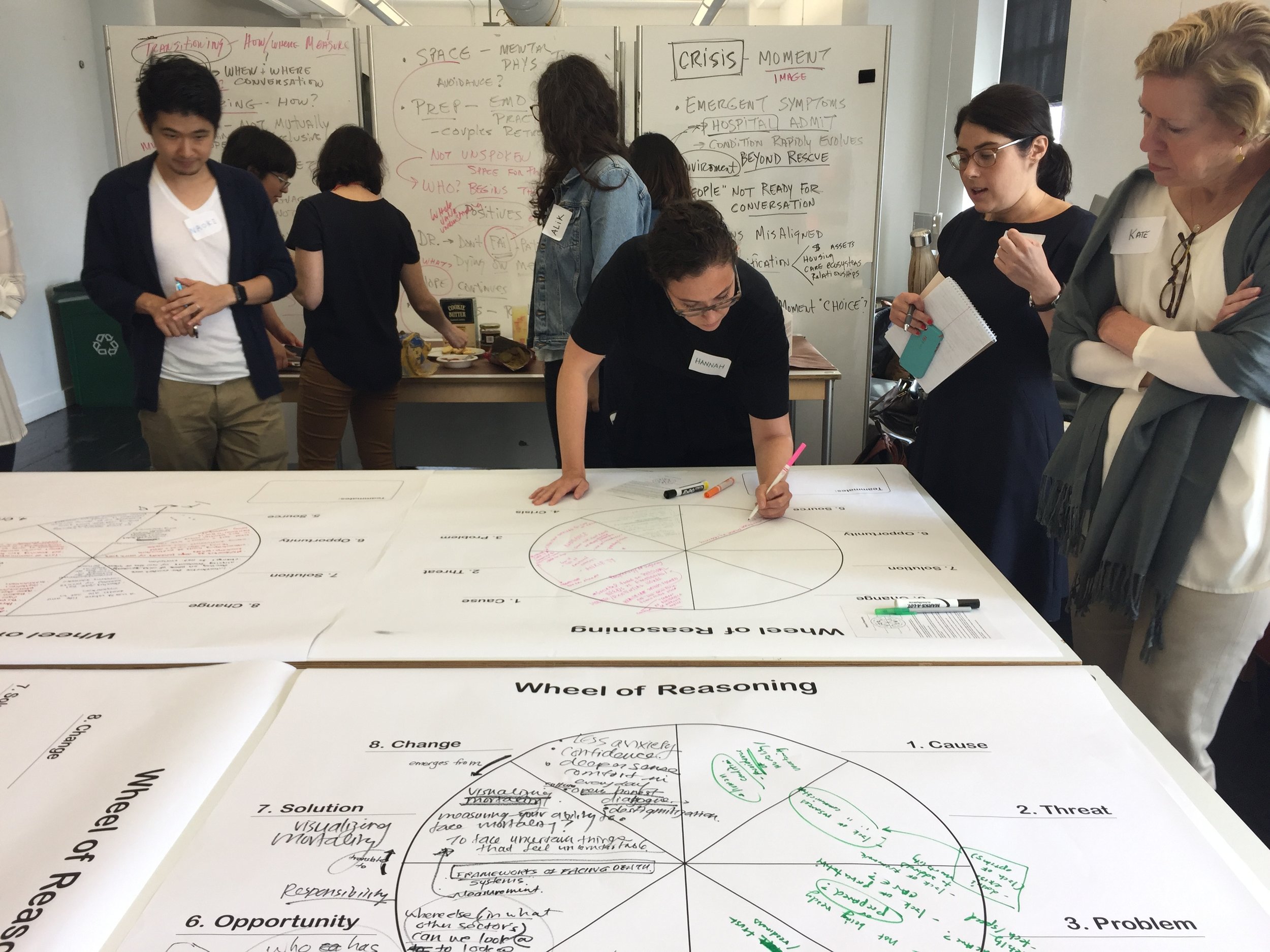

Through workshops with physicians, nurses, caretakers, patients, and healthcare strategists from Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital, like World Cafe, and tools, like the Wheel of Reasoning (developed by FreedomLab), key insights were revealed into how might the project help physicians and medical staff redistribute attention from logistics of care to being with dying; activate a conversational space where they can step outside of the distractions of options and hope for cure to an acknowledgment and empathy for the patient's life; and become aware of their intangible biases embedded in medical communication.

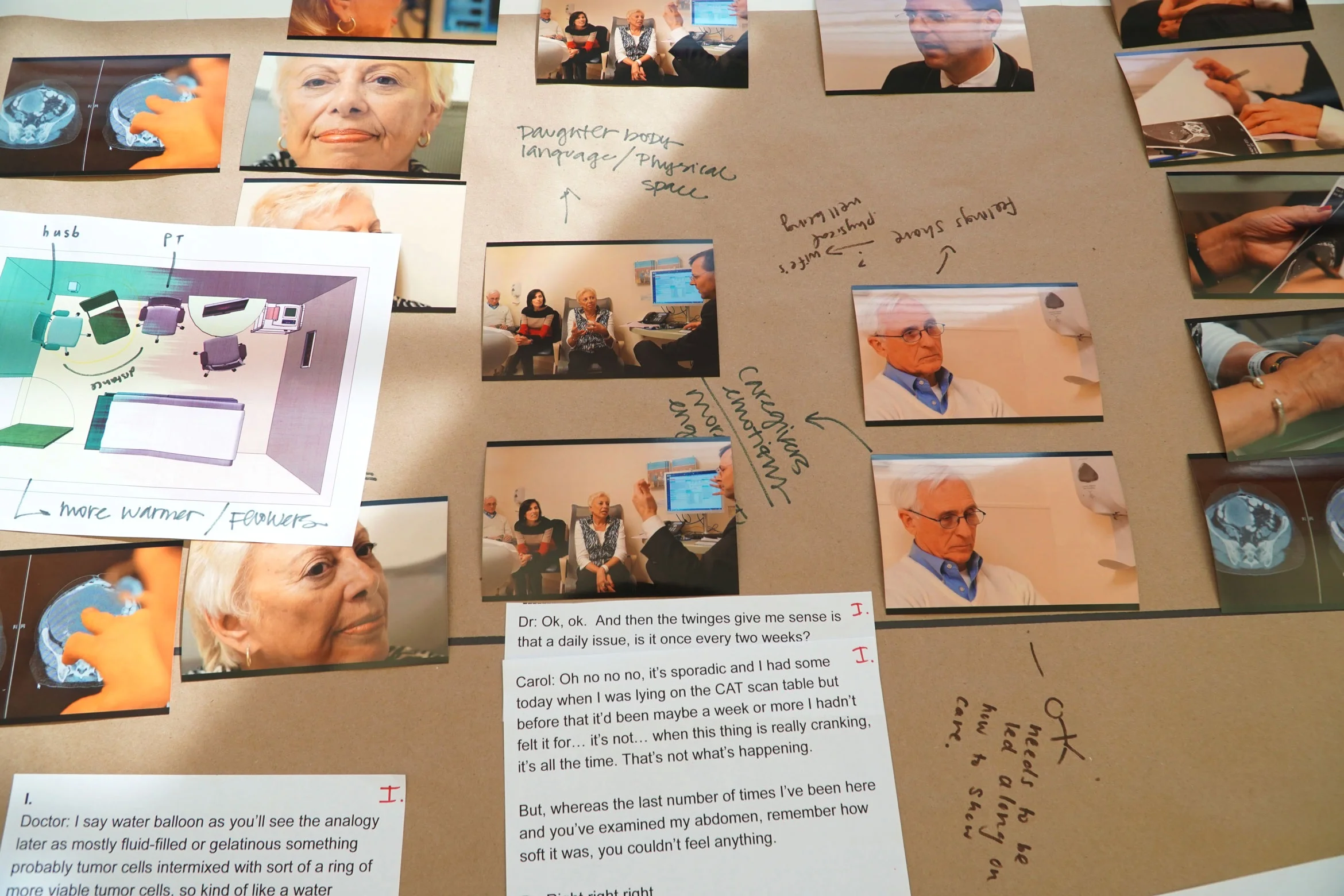

We ran two multi-stakeholder scenario workshops with patients and caregivers, using clips of a documentary called “End of Life” by John Bruce and Pawel Wojtasik. Participants were asked to watch the media piece and deconstruct events within the scenes through a co-creative process.

After the workshop, our team revisited the wheel of reasoning diagram, this time developing the wheel to highlight issues within the patient-family-doctor relationship. Insights from our studio workshops led us to approach the issue from the perspective of curative doctors, as they take on more of a “professional” leadership role in determining course of action around care.

We began to customize further research by working with medical educators and students, as our previous research revealed a potential leverage area for intervention in the early stages of training. We designed and ran recorded workshops involving doctor-patient role play simulations and vigil plan exercises (2 medical educators - palliative care and oncology, 2 teams of medical students, and a resident).

Then, we materialized our tools into a designed toolkit with self-guided instructions, which we tested with palliative care fellows at New York Presbyterian Hospital. We observed the session, conducted user feedback share outs and surveys, identified toolkit pain points, and assessed user perceived value of the toolkit.

Our process of coding transcripts from recorded workshops and interviews led to surprising insights. We discovered that the students’, resident’s, and oncologist’s discomfort with the uncertainty of death and their desire to rescue the patient were expressed through patterns in language.

Medical students participated in a recorded role-played conversation. The students were given a scenario to discuss how they would prepare for a cancer patient’s next consultation, whose condition was discovered to be terminal.

We applied an informal “grounded theory” approach to analysis by coding patterns in language and word usage from the recorded workshop and interview transcripts. Through this approach, we detected participant attitudes embedded in their use of language.

By dissecting apart the words doctors, students, and medical staff were using to talk about dying and death in hospital contexts or in their own personal dying experience, we discovered that an evidence-based approach could have a profound effect within a population of individuals who privilege direct observational facts.